How to Engage Diverse Populations in Clinical Trials and Vaccine Studies

After Karn Dhingra responded to an ad for a clinical trial seeking minority participants for a COVID-19 vaccine study in Houston, what followed was a seamless process: He gave his medical history and signed consent forms, received two rounds of shots, took his temperature daily and journaled his symptoms in the days that followed each round, and was compensated for his participation in the Novavax vaccine trial.

“They made it as easy as possible,” said the 41-year-old man, who identifies as Indian American. “I just had to show up.”

Including diverse participants in clinical trials has not always been a priority for medical researchers, but investigators are beginning to emphasize making clinical trials more inclusive and accessible. Testing new vaccines and developmental drugs on people of different ages, races, ethnicities, sexes, genders and socioeconomic backgrounds ensures the therapies will be safe and effective for different populations.

“We all want better drugs. We all want better health care. So why would we only be testing one part of the population when new treatments are good for everybody?” said Carol E. Breland, MPH, RRT, an adjunct professor in the University of North Carolina’s Gillings School of Global Public Health Leadership program, who teaches quality improvement and leadership in public health. “If people are hesitant about participating, they might feel hesitant about even taking the drug since they don’t know how it was tested, and risk not getting the advantage of the drug.”

Fostering relationships between research teams and diverse populations is the first step toward incorporating underrepresented communities in the clinical trial process.

Why Diversity Is Important in Clinical Trials

Broader trends are influencing clinical trials to include people of different races, genders, socioeconomic statuses, ages and disease states to ensure drugs are safe for the populations that will ultimately benefit from such treatments, once they are approved.

As stated in an article in Scientific American on the lack of racial and ethnic diversity in clinical trials, “if diverse groups aren’t part of these studies, we can’t be sure whether the treatment will work in all populations or what side effects might emerge in one group or another.”

Historically, minority groups and women have been underrepresented in medical studies. Lack of racial, ethnic, gender and age diversity is problematic because it results in findings that may not apply to all demographics.

“When trial participants are homogenous (e.g., primarily one gender, race/ethnicity or age group), findings may be skewed and result in a body of clinical knowledge that is not generalizable,” research on increasing diversity and overcoming barriers in clinical trials indicates.

However, Breland, who is passionate about promoting effective communication strategies for engaging underrepresented populations, said she has seen a shift toward more inclusive attitudes among investigators.

“All the drugs we take, the procedures we get, the new knee replacements—everything is dependent on research,” she said. “And if we don’t have a culture of inclusive research then we won’t get where we want to be, which is of course for everyone to have better health. And that doesn’t include just some people; it’s for everyone.”

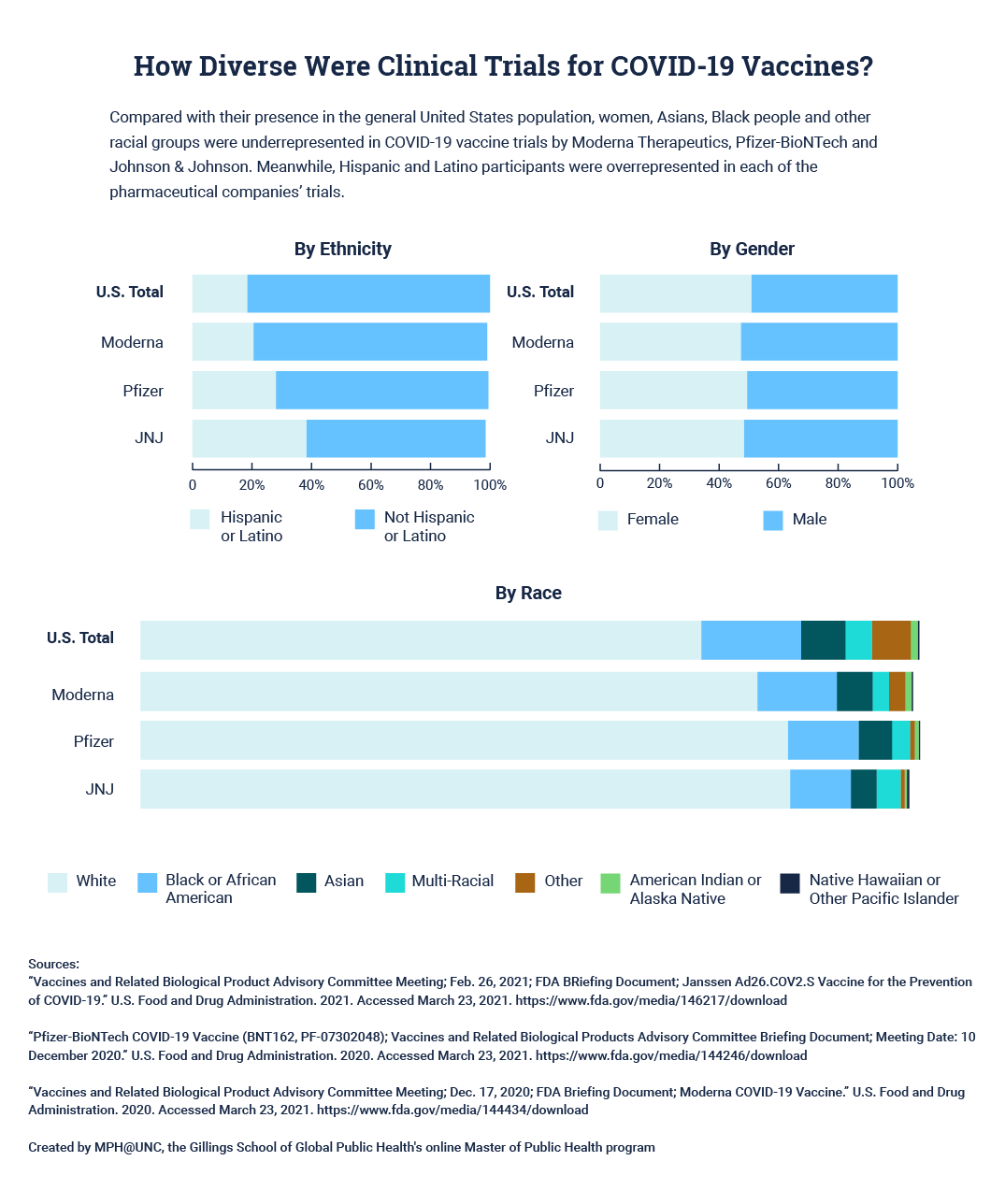

Though diversity efforts are improving, the data suggest more vaccine trials need clear diversity goals as minority groups continue to be underrepresented—and in some cases, women are overrepresented—in vaccine studies.

Moderna Therapeutics, Pfizer-BioNTech and Johnson & Johnson break down participation in their COVID-19 vaccine trials by ethnicity, gender and race. Some of the racial categories do not add up to 100% due to rounding errors. Click here for a tabular version of this data.

Clinical Trials and Diversity of Participants

Some minority groups are hesitant to participate in clinical trials because of historic abuses. One of the most well-known examples was the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, in which Black men were denied treatment for syphilis without their informed consent. Dr. Bill Jenkins, a Gillings School alumnus and epidemiology professor, blew the whistle on the Tuskegee syphilis study, managed the Participant Health Benefits program for survivors and helped obtain a presidential apology.

Another example is the Henrietta Lacks case, which centers on a Black woman who died from cancer in 1951. Her cells were used without her permission to start a cell line for medical research that is still in use today.

What Are Barriers to Diversity in Clinical Trials?

There are a number of barriers that discourage or prevent minority populations from participating in clinical trials. According to the aforementioned research in Current Problems in Cardiology and information from Breland, barriers to inclusive research include:

- Mistrust of the clinical trial process.

- Lack of information about trials.

- Scheduling, resource and transportation constraints among participants.

- Limited time as drug companies seek quick approval.

- Low literacy rates, including health literacy.

- Few or weak relationships between research programs and diverse communities.

What Are the Benefits and Risks of Participating in a Clinical Trial?

There are potential upsides and downsides to clinical trial participation, according to the National Institute on Aging.

BENEFITS MAY INCLUDE:

- Early access to potentially helpful treatments

- More frequent checkups and increased access to health care and resources for a disease

- Sense of altruism from contributing to medical research

RISKS MAY INCLUDE:

- Unknown side effects of an experimental treatment

- No improvement to health condition from the trial treatment

- Fallen hopes if a placebo is received

- Time commitments

Where to Find Clinical Trials

There are a number of websites, resources and physical sites where people interested in clinical trials can learn more about participating in them. Here are a few:

- Local teaching hospitals

- Large universities

- Health providers

- Disease-specific organizations, such as the Alzheimer’s Association, American Cancer Society or Parkinson’s Foundation

- ClinicalTrials.gov

- Center for Information and Study on Clinical Research Participation (CISCRP)

- North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute

- Research for Me

How Can Researchers Incorporate Diverse Communities in Clinical Trials?

During the clinical trial in which Dhingra participated, he recalled working with staff of diverse races and genders who were receptive to his questions about the trial process.

“Being really open and honest and transparent about everything, I think, is best,” Dhingra said. “Some communities are reluctant to participate in studies like this because of past history.”

Breland said the work to create more diverse trials should begin long before the trials themselves.

“Before you ever start recruiting you have to reach out to the community and be in that community before you can really start wanting people to help you,” Breland said.

It can be easy for investigators to become so wrapped up in their scientific work that they neglect to consider how to reach people to actually participate in their studies, she added.

“Making it as seamless as possible for anybody, regardless of your socioeconomic or racial background—I think that’s the most important thing,” Dhingra said. “Don’t make folks work really hard to do this.”

How Can Clinical Trials Increase Enrollment of Diverse Populations?

These strategies can help the medical community design and execute trials that are inclusive of participants of different races, ethnicities, ages, sexes and socioeconomic statuses.

1

BUILD RELATIONSHIPS BEFORE LAUNCHING STUDIES.

Investigators should partner with community leaders, houses of worship and other organizations to build trust and awareness in communities that could benefit most from their research project. Creating a community advisory board can guide research priorities by informing researchers of the issues that are most important to communities, Breland said.

2

ENGAGE IN OUTREACH AND EDUCATION AROUND TRIALS.

Investigators can seek grants to fund outreach efforts to reach diverse populations and educate prospective participants on the goals of the research. Advertising through a range of media outlets and using social media to target specific age groups can help researchers connect with diverse audiences. Researchers should be responsive to questions and concerns throughout the trial process.

3

ENSURE ACCESS TO TRIALS.

Partnering with local institutions and smaller clinics—in addition to large research centers—can help investigators make studies convenient to populations that do not live near major research institutions. Investigators should design trials to accommodate participants with schedule conflicts by, for example, offering early morning or late evening hours. Helping participants with transportation—perhaps by providing parking or bus vouchers—can improve access, and utilizing telemedicine appointments or mobile apps can boost attendance at follow-up appointments.

4

CONSIDER THE WHOLE PARTICIPANT EXPERIENCE.

Offering incentives, such as monetary compensation, can encourage participation in trials (though Breland cautioned against offering too much to avoid being coercive). Employing diverse staff at research facilities and on trial teams can help participants feel welcome. Researchers should also be respectful and treat all participants with dignity. In fact, Breland suggested investigators participate in other clinical trials themselves to better understand a participant’s experience.

How Diverse Were Clinical Trials for COVID-19 Vaccines? ↑

By Gender

| Populations | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|

US Totals | 50.8% | 49.2% |

Moderna | 47.3% | 52.7% |

Pfzier | 49.4% | 50.6% |

JNJ | 48.3% | 50.8% |

By Ethnicity

| Populations | Hispanic or Latino | Not Hispanic or Latino |

|---|---|---|

US Totals | 18.4% | 81.6% |

Moderna | 20.5% | 78.5% |

Pfzier | 28.0% | 71.4% |

JNJ | 38.2% | 60.3% |

By Race

| Populations | American Indian or Alaska Native | Asian | Black or African American | Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | White | Other | Multi-Racial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

US Totals | 0.9% | 5.7% | 12.8% | 0.2% | 72.0% | 5.0% | 3.4% |

Moderna | 0.8% | 4.6% | 10.2% | 0.2% | 79.2% | 2.1% | 2.1% |

Pfzier | 0.5% | 4.3% | 9.1% | 0.2% | 83.1% | 0.6% | 2.3% |

JNJ | 0.3% | 3.3% | 7.8% | 0.3% | 83.4% | 0.5% | 3.1% |

Citation for this content: MPH@UNC, the Gillings School of Global Public Health’s online MPH program.